This is the story of Caspar (also written as Kaspar) Hauser, a strange youth of about 16 who was found aimlessly wandering the streets of Nuremberg. Germany in 1828. Unable to speak more than a few words, he had been imprisoned for as he could remember in a tiny cell. Let us learn how the story began.

On a Monday in the year 1828 Georg Weichmann, a shoemaker of Nuremberg, Germany, noticed an oddly dressed youth of about 16 wandering aimlessly in the square near his home. The youth, a total stranger, looked like he might be drunk by the way he moved so uncertainly. Weichmann approached him.

The Mysterious Letter

The youngster handed Weichmann a letter addressed to the captain of the 6th Cavalry Regiment, then stationed in the Bavarian city. The shoemaker took the time to find out where the captain was housed, led the boy there, and left after ringing the bell.

When the door was opened by a servant, the youth handed over his letter and said in a broken dialect, “I want to be a soldier like my father was.” The captain was away, but his wife ordered food and drink to be brought to the young stranger, who looked worn out and could walk only with difficulty. He rejected what was offered, but when plain black bread and water were put before him, ate as though he were starved.

When asked who he was and where he came from, he seemed not to understand what was being said to him. To all queries he either repeated, “I want to be a soldier like my father was,” or grunted a few disconnected words such as “horse,” “home,” “my father” – all of which he seemed to have learned by heart. He frequently pointed to his feet and wept, as though in pain.

When the captain returned, he could get no further with the boy. The envelope addressed to him turned out to have two letters within, both of which added to the mystery rather than clearing it.

The First Letter

The introductory letter said that the writer, who did not identify himself, had had the child left with him on October 7, 1812, and had never let him go out of the house. It added: “If his parents had lived, he might have been well educated; for if you show him anything, he can do it right off.”

The Second Letter

The second letter, written to give the impression that it was from the youth’s mother to the writer of the first letter, was dated 1812, 16 years before. It said that the youngster’s name was Caspar, and it asked that he be taken to Nuremberg at the age of 17 because his dead father had belonged to the 6th Cavalry Regiment. Since the 6th Cavalry had been stationed in Nuremberg for only a short time, the letter could hardly have been written so long before. Both letters were believed to be forgeries.

Over To Police

The captain decided that the matter was one for civil authorities, and turned the youth over to the police. At the police station the same situation occurred. The youth made no sensible answers to questions, seeming to have no comprehension of what was going on around him. Sometimes he repeated his few stocks of words or pointed, weeping, to his feet. When a kindly soldier gave him a small coin he was delighted and called out, “horse, horse,” making signs that he wanted to hang the bright object around a horse’s neck.

His manner was that of a three-year-old child, but no one could decide whether he was a born idiot or some one who had lost his wits. A few even suspected that he might be an imposter. When provided with paper, pen, and ink he immediately wrote the name Caspar Hauser in a firm legible hand. He could write nothing else, and no more information could be obtained from him since his replies were irrelevant.

He ignored threats of punishment, showing neither fear nor defiance. Finally he was taken to a nearby prison for vagabonds and suspicious person; there he fell asleep instantly on a hard straw bed.

Other Possessions

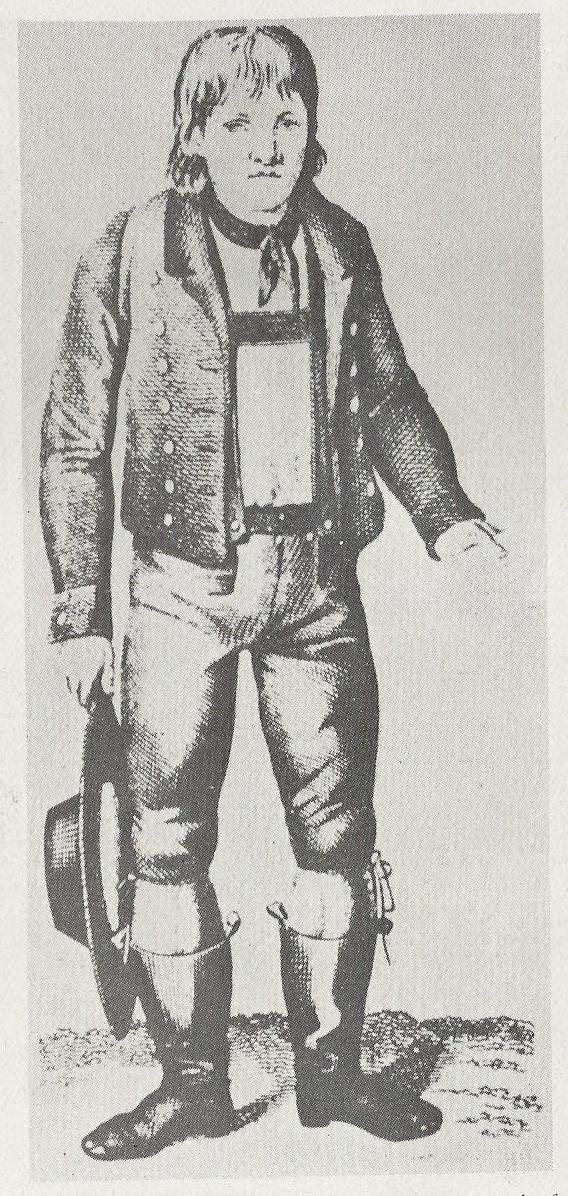

A part from the two letters, Caspar’s only possession were some pious tracts and the clothes he stood up in – worn shoes, a red leather hat lined with yellow silk, a black silk kerchief around his throuat, and a gray suit that looked as if it had been made from the cast-offs of a gentleman. In his pocket he had a white handkerchief with a red border and the initials C.H. worked in red.

When Caspar wept his face became ugly, like the puckered face of a crying baby, but when he smiled his face lit up so attractively that people said it was the face of an innocent child. The soles of his feet were as soft as a baby’s, as though he had never before worn hoes and never walked. In fact, he moved like a child learning how to walk, often losing his balance and falling.

The jailer became deeply interested in Caspar and put him in a room in his own apartment where he could watch him unobserved through a secret opening in the door. After careful observation the jailer decided that his charge was neither an idiot nor a madman nor an imposter. In his opinion Caspar was a child in experience and behaviour – if not in age – and he believed some great mystery lay beneath this unnatural state.

The Mystery

The story might seem like any other missing person’s story but there are many differences. It is not everyday that someone kidnaps a boy long years. What is the motive behind such an act where both the kidnapped and the kidnapper nearly waste two decades of their life. It certainly cannot be money.

Many people say that the boy was the missing prince of Baden by some, and an imposter by others, he was murdered by an unknown assailant in 183. Whatever is the truth, it got buried with the death of the boy and the enigma of Caspar Hauser would continue to exist.